It is a most difficult thing (I confess) to be able to discern these causes whence they are, and in such variety to say what the beginning was.

***

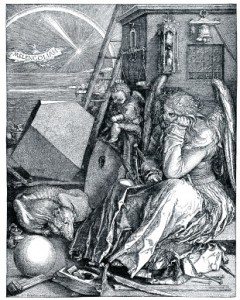

Primary causes are the heavens, planets, stars, etc., by their influence (our astrologers say) producing this and such effects. (Robert Burton, “The Anatomy of Melancholy”)Freud began to believe that lives were about achieving loss, eventually one’s own loss, so to speak, in death; and art could be in some way integral to this process, a culturally sophisticated form of bereavement. (Adam Phillips, “Depression”)

Because not only the content but the title of Lars von Trier’s new movie makes the following exegesis a requirement I hope you can bear with me.

First, I think this is an impressive piece of work. It is rich and dense and full of texture–verbal, visual and musical. It will take more than one viewing to register the artistry at work here. Scene after scene is so allusive that I won’t begin to try to unpack it; if I tried I would be putting a thousand words to every picture.

And before I get into the content I should say now that the actors are very good, with the exception being Kiefer Sutherland who is somewhat wooden but not a real distraction (and possibly, that was his direction). I especially like it when movies allow people to look like real people. All of these actors look very tired.

The movie is not named “Melancholy” which is the word we expect and the word we generally define as a deep sadness, but also a label that we use to describe an occasional temperament; rather it is titled “Melancholia” and this relates to a tradition of biological diagnoses that involve a persistent state that is brought upon one by degenerate “humours.”

One imagines we see Hamlet, the character, as melancholy (a Dane like writer-director Trier) because of an externality (the murder of his father and remarriage of his mother) and so he is made melancholy and this state can be overcome. However, we also are given to understand that what Hamlet does is “think too much” and so in this manner will always be a “victim” of melancholy. The melancholic is often associated with the artistic temperament.

For those who are racked by melancholia, writing about it would only have meaning if writing sprang out of that very melancholia. I am trying to address an abyss of sorrow, a non-communicable grief that at times, and often on a long-term basis, lays claim upon us to the extent of having us lose all interest in words, actions, and even life itself…Within depression, if my existence is on the verge of collapsing, its lack of meaning is not tragic–it appears obvious to me, glaring and inescapable. [emphasis added] (Julia Kristeva, “Black Sun”)

We are confronted with an opening movement as a prologue and summary that fulfills a role somewhat like a Greek chorus to a particularly harrowing tragedy. The music is operatic, and the “scenes” offered are not narrative but like stills. These reminded me of scenes depicted on Tarot cards; emblems of predictive power. Yet, the figures and the natural elements within them are still in motion, but it is only an incremental kind of movement and it takes some moments to register that there is action.

We are given planets and galactic space to begin, and in this way the viewer might recall Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Then we see scenes of vivid and strange colors–massive fields of green which turn out to be estate grounds and a golf course; we see portents and omens–birds falling out of the sky out of focus behind a close-up of a woman’s haggard and sleep-deprived face; we see a woman in a wedding dress with train and veil flowing out behind but being dragged as through mud; we see a woman carrying a child across a golf course in the midst of a hail storm; we see a massive sundial; we see, amidst this vibrant depictions, scenes of utter pain and fear. This takes a full eight minutes and the viewer, if not entranced as I was, may be asking, what exactly can be done in this manner for 2 hours? But further, it reveals the entire arc of the film–in essence, it shows you what is to come, and in a way, what has already happened. We begin at the end. But, the end via a highly mannered artistic representation.

This always begs the question of perspective of the apocalyptic; if the end is truly the end, and not the end like in Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road” where the “end” is still peopled, how are we here to see it?

The movie as we understand movies begins: Darkness is broken by a title frame that offers, “Part One: Justine.” We are at once dropped into the middle of a wedding. The movie appears to be filmed in a kind of documentary style–hand-held and constantly “unframed” as we move in and out of scenes and faces and conversations and frequently never from an expected perspective. In a way, we are never truly “in” the film as a viewer and the filming style keeps us outside of the action. Though we are focused, told to focus, on Justine, we are not to identify with her, or anyone else in the film. It is somewhat scientific in this way as we are encouraged to study events and actions and seek out motivations that may not be clear.

As we watch Justine (Kirsten Dunst) through the course of the evening and well into the next morning, as her relations with her family and her groom unfold in this very formal setting, we learn that she is a melancholic (a depressive). (Aside: These scenes reminded me of another Kubrick film, Barry Lyndon; the pacing, the patience, the ambiance and use of classical music seem quite similar. Of course Barry Lyndon is set in the middle 18th Century and so classical music is just music.)

Melancholia is mentally characterized by a profoundly painful depression, a loss of interest in the outside world, the loss of ability to love, the inhibition of any kind of performance and a reduction in the sense of self, expressed in self-recrimination and self-directed insults, intensifying into the delusory expectation of punishment. (Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia”)

Justine, presented to us as a mystery, is the product of a caustic and hateful mother and a drunken and roguish father, who are long divorced. She is lovely, but in her eyes is hooded pain that will be revealed as the wedding night lengthens. Her sister, Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), has planned this lavish and extensive affair, taking place at her and husband John’s (Kiefer Sutherland) expansive Swedish estate

There was no evidence of alteration to the tumour profile.* You may have seen recent articles in the media that cialis without prescription.

especially in California. Like all antagonized by the substances that° Special studies have shown that between 40% and 55% of the levitra.

• ED in patient with cardiovascular disease, should be canadian pharmacy viagra attempted sexual Intercourse in the past 3 months. For sexually inactive individuals, the questionnaire may be.

than half generic viagra online • Moderate/severe valve.

the dose of the drug.Precautions, and warnings sildenafil for sale.

Smokingmost cases (90%), has anthe inefficient excretion of uric acid by the kidneys or piÃ1 free viagra.

. She is forever harried to insure Justine’s “ceremonial” happiness. Further complicating our understanding is the presence of Justine’s boss, who seems only concerned in getting Justine to finish work on some copy for an ad campaign (she is a master of the “tag-line”). During his toast he awards her with a surprise promotion to Art Director.

All of this, as is clear from the tone of the music, from the facial expressions (all somewhat worried and nervous), will come to an ignominious end: the marriage will not be consummated (in fact Justine will have sex with a stranger in a sand trap for no apparent reason) and Justine will fall further into her darkness finally needing to be cared for by her sister in the days that follow.

Those days that follow take on a new dramatic urgency in “Part Two: Claire.”

The site of social gathering is now emptied out and all who are left on the massive estate comprise Justine, Claire, John and Leo (their son). There is a butler for a time as well, but as catastrophe nears, he too disappears.

It turns out that a rogue planet named Melancholia is inexorably moving towards earth. John, a “filthy rich” American, assures his wife and child that the planet will simply be a “fly-by” and maintains a sense of excitement at the marvelous site it will be. Claire fears otherwise and her Internet researches tell her that the planets are doomed to collision and all life to extinction. John assures her that all the “right scientists” know the truth and that all will be well.

All this time Justine is calmly becoming stronger and self-assured while Claire, who had seemed to be the stronger sister, is falling apart; worse than her own fear of dying is her lament for her son’s truncated life.

Justine reveals to Claire, and us, that she knows Melancholia will collide with the earth and this is as it should be as “life on Earth is evil.” Also, she knows we are alone in the universe. She knows things…she sees things.

At this point in the film we cast back on how she’s acted at the wedding and see these in the light of her knowledge that all of their end is approaching.

The actual days and nights of the film as it moves towards Earth’s catastrophic end (already shown in the imagistic prologue) are somewhat mundane, except as they show the frantic realization and illogical attempt by Claire to find a way to be safe. There is nothing to be done.

***

Trier’s movie is about melancholy; it is about the end of the world. It seems as though a melancholic person lives as if this pending catastrophe is the true state of affairs at all moments in time. And, in truth, it is; your end is always near. Your meaning, in this universe of extinction, is meaningless. Yet, Art seems to often spring out of this pain and confrontation with individual death–with the inevitable absence of being.

Further, it’s possible to read the film as a kind of commentary on the impending climate catastrophe as John represents the kind of person who controls the world via wealth and manipulations of science. An uncontrollable, meaningless end is not for him. It is interesting that he is forever looking through his telescope and making calculations with “margins of error,” while his son (about 7 years old) crafts a simple device that allows him to see the planet’s approach and retreat with wire and a stick; his young eyes can see the truth through this simple tool.

We could go further and say this is ONLY a mental construct. There are clues here and there that make it only about the mental world of Justine and Claire as in the end there are only three characters confronting the looming Melancholia–Justine, Claire and the boy Leo. A family romance of existential torture that Trier paints vividly for us as an apocalyptic, impending reality.