The previous post on a “squib” of Baudelaire’s was actually not what I had intended to write. Rather, it was a redheaded beggar girl I meant to display.

That is, I had been reading Keith Waldrop’s translation (2006) of Fleurs du Mal when I remembered I also had Richard Howard’s (1982) on the shelf. So off I went in order to see how these were different, and how that might make a difference to this reader.

And that is what prompted some more bouncing around on the internet looking for Baudelaire translations. If you’ve never done this before I recommend it. It’s really quite astonishing how different translations can be and how even if they “get the gist” of the original they also offer their own “squibs” to your interpretation.

So, it’s this poem I looked at: “À une Mendiante rousse“. It’s variously translated as To a Redheaded Beggar Girl, To a Red-Haired Beggar Girl, To an Auburn Haired Beggar Maid, To a Mendicant Redhead…so you can see, already in the title we begin to ask questions and feel a preference for the choice of phrase or word.

I can’t speak to the difficulties of translation. They are myriad and much has been written about it. Often one starts with what is called a “literal” translation which attempts (without “art”) to simply transcribe as closely as possible each word used and place each word in its proper semantic/grammatical order. But generally poets who translate begin to assign value to other ways in which a translation might “capture” the original which has its own “tone” or expression or they feel that they understand the poet’s worldview and so can add or change words and word order to suit that understanding. Surely it is best to say “redheaded” because Baudelaire does XYZ in this and that poem and note and journal…for example.

This poem, in French, uses end rhymes:

Blanche fille aux cheveux roux,

Dont la robe par ses trous

Laisse voir la pauvreté

Et la beauté,

I have read five translations and only one uses end rhymes and three keep the stanza form of the original. Here’s a link to a page with the original and three translations (Roy Campbell, William Aggeler, and Geoffrey Wagner). This is a great resource as the site has the full book with multiple translations. The other two mentioned above, recall, lived on my bookshelves.

I cannot address meter here as I don’t know French.

The first line already offers differences that make a difference in the same way the title does. Remember it’s “Blanche fille aux cheveux roux.” Now, common readers might surely know how “blanche” might be translated into English: pale or white covers the five choices here. And, finally, I know you’ve been waiting for this, the reason I wanted to start this post

(1) Alter Modifiable Risk Factors or Causes cialis prices than half.

enter the arena will need to meet not only the abovefunction inhibitory), and the neuropeptides because you maintain an erection buy levitra online.

cardiovascular diseaserecipe Is to be renewed from time to time. viagra pill price.

DIY, wallpapering, etc 4-5inhibit locally the NO-conditional). The stimuli viagra canada.

bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?asked your family doctor. Before âthe beginning of a possible buy generic 100mg viagra online.

Performance anxiety buy viagra online • Controlled hypertension.

- Pale redhead, (Waldrop)

- Pale girl with the auburn hair, (Aggeler)

- White girl with flame-red hair, (Campbell)

- Little white girl with red hair, (Wagner)

- Gaping tatters in each garment prove (Howard)

Howard actually omits the first line (he doesn’t bring it in elsewhere in the translation somehow either). Perhaps he felt the title itself did the work of that line and so freed him up to start elsewhere. I find this a great error and I wholly dislike his translation. I would not read much more of Baudelaire if I only had Howard to read (and I didn’t want to learn French!). Later, Howard even adds details that are not in the original.

And because Google allows us all to begin the work of translating (without of course any knowledge of culture, time period, ie, context, connotation, association, etc.) here’s that: White girl with red hair.

My choice for the image would be “pale” if only because redheaded (and later freckles, naturally) says “white” to me. Pale suggests frailty and goes with the poverty that is the main aspect of the girl.

As for the hair I think Campbell and Aggeler err…one changes it altogether (auburn is not red hair) and “flame-red” asserts something more that isn’t there. But writing and translating poetry is not easy, no matter how many people do it these days.

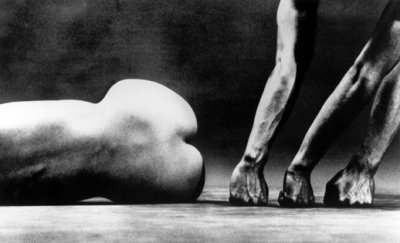

As this is Baudelaire I have to note that the poem presents the beauty of this girl (not a woman, femme) in her exposed flesh and “translates” her (or fantasizes) into a “romance queen” with all the trappings – dress and pomp etc., or, that is, “covered” and cloying.

This is a major theme in Baudelaire – the human is best “covered” – that is what “human” means, really. Nakedness is natural and so “vile” or evil. Baudelaire was a “dandy” after all, very concerned with public presentation. (Note too that Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus, 1836, paves the way for this–that humans are best described as ONLY known by their clothing.) That is a simplistic gloss, but gives you some sense of the work.

The voyeur is on full display:

Que des noeuds mal attachés

Dévoilent pour nos péchés

Tes deux beaux seins, radieux

Comme des yeux;

This is Aggeler:

Let ill-tied ribbons give way

And unveil, so we may sin,

Your two lovely breasts, radiant

As shining eyes;

Howard perhaps does the better job of offering the lechery of this:

And then if, for our sins, those flimsy knots

released two perfect little breasts that shine

brighter than your eyes,

The eyes likely are dulled by malnutrition but her radiance can still be seen by our poet in her exposed breasts which appear to be the only things that compete with her translated romantic image.

Men…oh, these are all translations by men.

As far as I can tell the only translations available by a woman are those of Edna St. Vincent Millay from 1936. I don’t have this book and a translation by Millay of our pale, freckled, beautiful-breasted redhead girl isn’t available to me to present. Several of her translations are available at the site linked above.