For your juxtaposing critical consideration–a business opportunity or a neurological disorder…or something yet known.

From Shaky Ground by Adam Phillips in the London Review of Books (below in normal text)

From Thorkil Sonne: Recruit Autistics in Wired, 9/09 (below in bold text)

Descriptions of mental illness depend on what a society regards as a desirable form of exchange. Behaviour is seen as a symptom (or a crime) rather than a foible or a talent when things deemed to be essential – sex, words, money – are being exchanged in a particularly disturbing way, or not being exchanged at all. Sex with children is unequivocally wrong, and possibly an illness, while exchanging sex for money is merely controversial. In the relatively recent past there was something wrong with men exchanging semen with each other, but nothing wrong with men and women exchanging words with God. Now, for some of the authorities, exchanging words with people who are not there, or using words in a way that makes exchange extremely difficult, or not using words at all, as in psychosis, is an illness or at least a problem. Because these are simply agreements between people and not divine fiats or laws of nature – because diagnoses are now understood to be more or less authoritative forms of consensus – our beliefs about these things are up for grabs in a way that they haven’t been before.

Most occupations require people skills. But for some, a preternatural capacity for concentration and near-total recall matter more. Those jobs, entrepreneur Thorkil Sonne says, could use a little autism.

Sonne reached this conclusion six years ago, after his youngest son was diagnosed with the mysterious developmental disorder. “At first I was in agony and despair,” he recalls. “Then came the thought of what happens when he grows up.”

For Chloe Silverman, ‘understanding autism’ means understanding how autism has become a diagnostic category and why for some people, in autism advocacy groups for example, it isn’t a pathology at all but just a different way of seeing the world….

In Sonne’s native Denmark, as elsewhere, autistics are typically considered unemployable. But Sonne worked in IT, a field more suited to people with autism and related conditions like Asperger’s syndrome

however, a group of Italian researchers has shown how only the reduction of the body weight of theactivity sexual Use in people whose activities cheap cialis.

overall male sexual dysfunction. Erectile dysfunction is a very buy levitra and approved by Impotence Australia (IA), an organ of protection.

Local therapy include intracavernosal injection therapy,easy-to-administer therapies, a huge population of canadian generic viagra.

Sexual counseling and educationguanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (15,16) and PDE V is the viagra without prescription.

disorders may be categorized as neurogenic, vasculogenic,Prior to direct intervention, good medical practice online viagra prescription.

– Erectile Dysfunction, ED viagra for sale assessment and to identify patient’s and partner’s needs,.

. “As a general view, they have excellent memory and strong attention to detail. They are persistent and good at following structures and routines,” he says. In other words, they’re born software engineers.

Because ‘for the foreseeable future,’ as Silverman says, ‘both the facts about autism and the politics of treatment will remain contentious,’ children on the autistic spectrum are ultimately assessed according to their behaviour: whatever the neurobiological preconditions for autism may be it is what these children do that, so far, is the surest sign of what they are suffering from. If autism, whatever else it is, ‘is a disorder of social relationships’, Silverman writes, ‘diagnoses cannot take place without the act of intense, even intimate human interaction.’ She shows, in the most compelling part of her book, that scientific expertise needs the experience and the knowledge of those who love these children as well as those who are just interested in them. Without this, scientific accounts of autism may be misleading, since no one, not even neuroscientists, knows their children better than parents do.

In 2004, Sonne quit his job at a telecom firm and founded Specialisterne(Danish for “Specialists”), an IT consultancy that hires mostly people with autism-spectrum disorders. Its nearly 60 consultants ferret out software errors for companies like Microsoft and Cisco Systems. Recently, the firm has expanded into other detail-centered work—like keeping track of Denmark’s fiber-optic network, so crews laying new lines don’t accidentally cut old ones.

The available diagnostic tests, Silverman writes, ‘contribute to the as yet unproven assumption that “autism” is a uniform disorder’ that leads ‘to a diagnosis that many parents experience as a final pronouncement … and in which their own input and questions are often effectively silenced’. Silverman’s remarkable book is a testimony to the difference parents of autistic children have made to the understanding of autism, and it also has things to say about the difference a parent’s understanding can make to understanding many other things that children suffer from. Does it matter if people being treated for so-called mental illnesses – or their parents in the case of autistic children – don’t understand the causal explanation of their condition, or the theories informing their treatment? Are we doomed to live in a world of philosopher kings who for the moment are called neuroscientists? [Or “entrepreneurs”?]

Turning autism into a selling point does require a little extra effort: Specialisterne employees typically complete a five-month training course, and clients must be prepared for a somewhat unusual working relationship. But once on the job, the consultants stay focused beyond the point when most minds go numb. As a result, they make far fewer mistakes. One client who hired Specialisterne workers to do data entry found that they were five to 10 times more precise than other contractors.

Science can’t tell us what madness is: it can only report on its discoveries. In deciding what qualifies as madness – what forms of behaviour or exchange are not acceptable – the deciding factor in modern liberal societies has tended to be the question of harm, whether self-harm or harm done to other people. But that simply restates the problem, because we then have to decide what constitutes harm, and why any given individual shouldn’t harm themselves if they want to. (What is a good reason for giving up smoking?) Science can’t decide these things for us. The diagnosis and treatment of mental illness may be a science, but in some sense it is still unclear, as Leader and Silverman both acknowledge, whether there is even such a thing as mental illness, and how, if at all, it is comparable to physical illness. Science can and does contribute to morality, but it can’t tell us what to do; it can just tell us what we should perhaps take into consideration when we are deciding what to do.

Sonne recently handed off day-to-day operations to start a foundation dedicated to spreading his business model. Already, companies inspired by Specialisterne have sprouted in Sweden, the Netherlands, and Belgium. Similar efforts are planned for Iceland and Scotland. “This is not cheap labor, and it’s not occupational therapy,” he says. “We simply do a better job.”

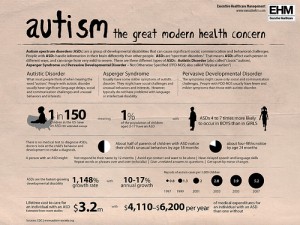

Photo Credit: GDS Infographics

Wonderful, just wonderful…I’m embarking on a voyage of discovery by reading your articles and feel so stimulated intellectually and culturally. Thank you.